Click here for an index of all “Lomo Manifesto” posts.

As I asserted in Lomo Manifesto Part 1, architects love dichotomies. Well known examples such as Discipline and Practice, Avant Garde and Kitsch, and Duck versus Decorated Shed have been used as scalpels to cut a category in half in order to see what its insides can show us.

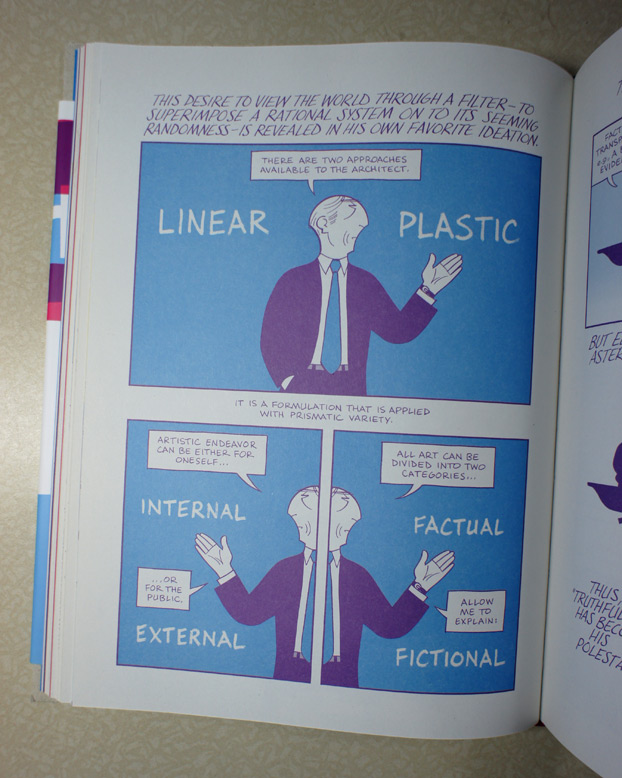

The tendency of architects to rely on this method of categorization is lampooned in David Mazzucchelli’s graphic novel Asterios Polyp as the “desire to view the world through a filter – to superimpose a rational system onto its seeming randomness.”

In several past LoMos posts I have characterized architectural elements, for example, the roofs of the featured projects in the previous post, as “Jaunty.” The term is used here as a technical term, signifying one pole in the “Jaunty vs. Butch” dichotomy. Conceived out of analysis of the problematic reception of Modernism in architecture on the part of the general public, this formulation proposes a divide between two tendencies within Modernism – the Butch, and the Jaunty.

The word “jaunty,” meaning “sprightly or lively in manner or appearance,” is an old word derived from the French gentil. “Butch,” meaning “notably or deliberately masculine in manner or appearance,” traces back only to the 1940s, and was borrowed from a nickname sometimes given to men in the butchering trade. The qualities of Jaunty and Butch in design cannot be precisely defined, as they are in the nature of tendencies or sensibilities. The terms are not mutually exclusive, but the Butch is characterized by rigor, austerity, cultural legitimacy, power, single-mindedness, toughness, and perfectionism. The Jaunty is characterized by relaxation, playfulness, color, inclusiveness, commerciality, cultural profligacy, compromise, and asymmetry.

Architectural styles tend to divide neatly along these lines. Brutalism is clearly Butch, whereas most lomo styles, such as Googie and the Polynesian Gabled, are Jaunty. The work of Modern designers also tends to adhere to one side or the other. The Jaunty tradition includes Charles and Ray Eames, John Lautner, George Nelson, and Morris Lapidus. The Butch team is filled out by Lou Kahn, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, and in extremis, Giuseppe Terragni. Others, such as Marcel Breuer and Eero Saarinen, seem capable of reconciling the two tendencies and sit in both camps.

The Jaunty and Butch sensibilities cannot be reduced down to a formula, but their common compositional characteristics are describable.

These compositional principles apply equally to graphic design as they do to architecture. Typefaces can have either a Jaunty or Butch character, and lower-case letters tend to have a jauntier feel. Bank Gothic, the most Butch font, is a scourge of architecture students’ work and plagues our schools; it is most appropriately used in the titles of scary movies about the apocalypse. Tyler Goss’s 2004 work “Bank Gothic Bomb” protested its overuse. Comic Sans, on the other hand, tries very hard to be Jaunty; however I recommend a nice, tightly kerned Modernist sans-serif as a better evocation of the Jaunty mood.

These characterizations of the Jaunty and Butch echo the positions espoused by Robert Venturi in “Nonstraightforward Architecture: A Gentle Manifesto,” at the front of his 1966 Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture. Venturi went to Rome, looked around, and came back and wrote, “I am for messy vitality over obvious unity” (22). It took considerably less effort and sophistication for me to open my front door, look at the dingbat apartment buildings, and advocate the Jaunty over the Butch.

An alternative formulation of this family of traits is “Ludic Modernism,” the subject of a 2010 exhibition in Brussels. From its accompanying catalog:

The post-war years are remembered as an era of optimism, with full faith in progress and confidence in the future. Architecture and design so imbibed this atmosphere that they spawned Ludic Modernism, a style marked by forms and colours of extraordinary joviality and freshness (4).

The term “ludic,” a fancy word for “playful,” hits the note accurately but lacks the implicit sexual politics of “Jaunty vs. Butch.” These sexual-political overtones may seem flippant, but in fact they are essential – the Butch represents hegemonic masculinity, and the Jaunty can function as a form of resistance.

The idea of Jaunty and Butch was conceived as a latter-day response to the anti-Modernist critiques of the 1970s, when Modernism as a whole was criticized for being harsh, windswept and unpopular, as discussed in “Lomo Manifesto Part 3: Lomo versus Pomo.” These criticisms were well earned by Butch architecture; Jaunty Modernism, however, provided abundant counterexamples that ought to have redeemed Modernism and could have provided an avenue of forward progress without the wholesale rejection of Modernism that led to the cul-de-sac of Postmodernism.

Among legitimate or academic architects, there is still felt a pressure to maintain Integrity through being Butch, and to reject the Jaunty as a form of Selling Out. Some of the best Modern architecture, like the Team Ten stuff, sustained both tendencies; but Peter Zumthor’s proposed remake of LACMA, combining a Jaunty roof shape with a Butch everything-else, proves that a little Jaunty cannot always redeem the harrowingly Butch. By implication of this post and of the Lower Modernisms project in general, designers should strive toward Jaunty Modernism and resist the tendency towards the Butch. The Butch might even be definable by its lack of popularity – it is the architecture that is loved only by architects.

***

Bibliography:

Berckmans, Caroline, Pierre Bernard & Anne-Sophie Walazyc. Ludic Modernism in Belgium. Brussels: Atomium, 2009.

Mazzucchelli, David. Asterios Polyp. New York: Pantheon Books, 2009.

Venturi, Robert. Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture (The Museum of Modern Art Papers on Architecture, Vol. 1). New York: MOMA, 1966.

Leave a Reply to Alan Hess Cancel reply