The term “Brutalism” refers to what was both a movement and a style in Mid-Century Modern architecture. The architects Alison and Peter Smithson had laid claim to the term in the early 1950s, hoisting the “New Brutalism” as an emblem of their idealistic, ethically minded brand of Modernism; Reyner Banham then asserted his critical ownership of the term in a 1955 essay on the Smithsons entitled “the New Brutalism,” in which he concluded that the three defining elements of the New Brutalism were “1, Memorability as an Image; 2, Clear exhibition of Structure; and 3, Valuation of Materials ‘as found’” (15). Despite Banham’s efforts to define Brutalism according to this set of relatively flexible and abstract principles, in the long run Brutalism is remembered less as a movement and more as a style. The defining trait of this tough, uncompromising style is its use of the exposed, rough-textured, cast-in-place architectural concrete evoked by Brutalism’s name, a play on a French term for rough concrete, beton brut.

Similarly characteristic of the Brutalist style was its deployment of circulation elements. On loan from Le Corbusier, Brutalist megastructures employed “streets in the sky” as imageable circulation components, freed from the ground plane and appended to the exterior of the building. Such elements had been used on the Smithsons’ influential, unbuilt 1952 Golden Lane housing project, and contributed to the dramatic character of well known built projects in the Brutalist style including Park Hill, Sheffield, and Queen Elizabeth Hall, London, both designed by Council architects. European projects such as these were widely published and by the 1960s, an architectural style combining exposed concrete with oblique geometries and dramatized circulation was well established in the United States, a common choice in the playbook of architects designing university and public buildings, particularly in the East.

Banham described Golden Lane as “having put the idea of the street-deck back in circulation in England” and positing that in the Smithson’s unbuilt Sheffield University project, “topology becomes the dominant and geometry becomes the subordinate discipline” (14-15). As with his effort to name the three defining elements of Brutalism, there is a conflict between the intellectualized ideal and the perceived result – Banham portrayed streets in the sky as a complete rethinking of the architectural problem as one of topology rather than one of geometry; or less jargonily, an architecture based on the experience of circulation rather than on the disposition of mass. In effect, however, this may just be an architecture in which walkways take the place of ornament as a means of architectural decoration.

The Casa Serrana Apartments at 3416 Manning Avenue in Cheviot Hills are the result of a melding of British-style Brutalism with California-style Dingbat architecture. Built according to the Assessor’s records in 1966, Casa Serrana shows the unmistakable influence of Brutalism, most conspicuously in its gratuitous, free-standing stair tower connected back to the building by a pair of flying walkways. This building shows the abstract geometries and expressed circulation of Brutalism, but lacks the materiality; this is a Stucco Brutalism, a Brutalism for Los Angeles, in which cement plaster is employed as the economical alternative to cast-in-place concrete. This yields a Lower Modern version of Brutalism, hitting some of Brutalism’s stylistic notes but lacking both the “clear exhibition of structure” and “valuation of materials ‘as found’” referenced in Banham’s formulation of an ethically motivated Brutalism.

At the time of its construction, the 108-unit Casa Serrana was poised proudly on a slope with an outlook over the Santa Monica Freeway, which had opened a year earlier in 1965, as though Casa Serrana’s designers had thought a view of the exciting, new freeway to be desirable. The stair tower and its flying walkways create a dialogue with the circulation pathway of the freeway across the street; regular users of the Santa Monica Freeway have probably noticed Casa Serrana. Bird’s-eye image on loan from Google Maps.

Blocky and asymmetrical, Casa Serrana vaguely resembles the Dessau Bauhaus in its massing, but in lieu of the Bauhaus’s smooth and transparent surfaces, Casa Serrana’s exterior is wrapped in balconies and exterior hallways, Dingbat-style. Built contemporaneously with the Dingbats that surround it, Casa Serrana is a kind of Brutalizing Mega-Dingbat.

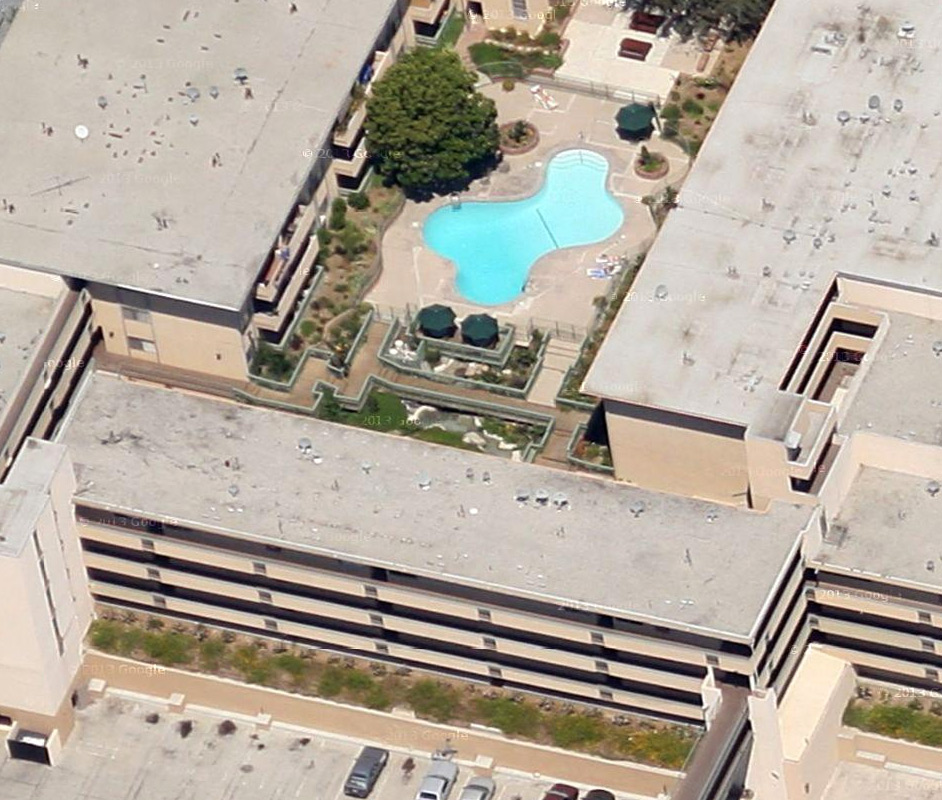

Zooming in at the center of this image exposes yet another mode of deployed circulation – lofted above a boulder-strewn synthetic creek of the sort encountered at miniature golf courses is a stepped, wood-plank walkway negotiating the exterior grades. An amoeboid swimming pool stretches to fill the courtyard nicely, another move from the California Modern architectural playbook rather than a Brutalist one.

In this view from the north, the twin flying bridges look almost impossibly thin. Multiple levels of carpark terrace the grade along Manning Avenue. Viewed from the front, there are two particular aesthetic moves intended to soften the tough Modernism of Casa Serrana – the beige paintjob and the Spanish-tile hat that tops the stair tower; one strongly suspects that these decisions were both contrary to the original conception of the architect, who was probably an eager enthusiast of British architecture publications and hoping to design something similarly earnest, serious and publishable. I suspected it might look better in black-and-white.

Transforming this image into a black-and-white photograph, simulating the grainy, analog look of Brutalism’s preferred medium, strips away the beigeness and dials up the abstraction. Now Casa Serrana would not stand out quite so much amongst its legitimate Brutalist second cousins featured on the “FUCK YEAH BRUTALISM” Tumblr feed.

The stair tower’s tile-roofed hat definitely possibly could be an afterthought or later modification. It is an outrage to the stripped aesthetic elsewhere throughout the building, but also an amusing, domesticating touch tempering the most visible, billboard-like part of Casa Serrana, gamely advertising to westbound drivers on the Santa Monica Freeway. This front element of the building, instead of stucco, was constructed with concrete masonry units, a poor-man’s alternative to poured concrete. The units are “precision score” block, giving an appearance of stacked squares rather than a conventional brick bond. The parking deck exterior walls are supported by rows of actual buttresses, and the combination of tower with the imposing, slot-windowed street wall suggests castle or fortress.

Casa Serrana’s three stories of apartments are terraced up the hill, with those on the left side offset one level from those on the right. At the center of the image, an element projects two levels above the roof like a lookout tower, its purpose inscrutable, perhaps containing an elevator doghouse. This last image has been rendered black-and-white again, which by removing the beigeness tends to dematerialize the architecture and emphasize the geometry; the horizontality of the architectural elements harkens back to the early International Style. I am only using Photoshop to tweak the appearance of this building, but the effect is instructive. What is important for designers of cheap buildings to know is that this works in real life, too – consider Michael Maltzan’s technique of painting stucco buildings bright white, an expedient move which likewise dematerializes an architecture and emphasizes its geometry.

***

Bibliography:

Banham, Reyner. “The New Brutalism.” Originally published in Architectural Review, December 1955. Quoted in Clog, February 2013, “Brutalism.”

Leave a Reply to James Black Cancel reply